Maturity Model

26 August 2014

A maturity model is a tool that helps people assess the current effectiveness of a person or group and supports figuring out what capabilities they need to acquire next in order to improve their performance. In many circles maturity models have gained a bad reputation, but although they can easily be misused, in proper hands they can be helpful.

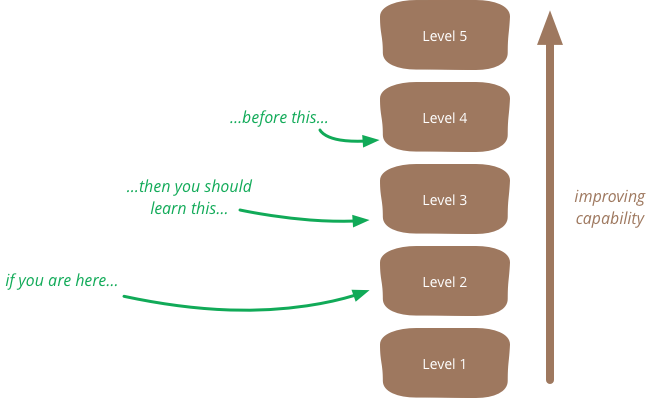

Maturity models are structured as a series of levels of effectiveness. It's assumed that anyone in the field will pass through the levels in sequence as they become more capable.

So a whimsical example might be that of mixology (a fancy term for someone who makes cocktails). We might define levels like this:

- Knows how to make a dozen basic drinks (eg “make me a Manhattan”)

- Knows at least 100 recipes, can substitute ingredients (eg “make me a Vieux Carre in a bar that lacks Peychaud's”)

- Able to come up with cocktails (either invented or recalled) with a few simple constraints on ingredients and styles (eg “make me something with sherry and tequila that's moderately sweet”).

Working with a maturity model begins with assessment, determining which level the subject is currently performing in. Once you've carried out an assessment to determine your level, then you use the level above your own to prioritize what capabilities you need to learn next. This prioritization of learning is really the big benefit of using a maturity model. It's founded on the notion that if you are at level 2 in something, it's much more important to learn the things at level 3 than level 4. The model thus acts as guide to what to learn, putting some structure on what otherwise would be a more complex process.

The vital point here is that the true outcome of a maturity model assessment isn't what level you are but the list of things you need to work on to improve. Your current level is merely a piece of intermediate work in order to determine that list of skills to acquire next.

Any maturity model, like any model, is a simplification: wrong but hopefully useful. Sometimes even a crude model can help you figure out what the next step is to take, but if your needed mix of capabilities varies too much in different contexts, then this form of simplification isn't likely to be worthwhile.

A maturity model may have only a single dimension, or may have multiple dimensions. In this way you might be level 2 in 19th century cocktails but level 3 in tiki drinks. Adding dimensions makes the model more nuanced, but also makes it more complex - and much of the value of a model comes from simplification, even if it's a bit of an over-simplification.

As well as using a maturity model for prioritizing learning, it can also be helpful in the investment decisions involved. A maturity model can contain generalized estimates of progress, such as “to get from level 4 to 5 usually takes around 6 months and a 25% productivity reduction”. Such estimates are, of course, as crude as the model, and like any estimation you should only use it when you have a clear PurposeOfEstimation. Timing estimates can also be helpful in dealing with impatience, particularly with level changes that take many months. The model can help structure such generalizations by being applied to past work (“we've done 7 level 2-3 shifts and they took 3-7 months”).

Most people I know in the software world treat maturity models with an inherent feeling of disdain, most of which you can understand by looking at the Capability Maturity Model (CMM) - the best known maturity model in the software world. The disdain for the CMM sprung from two main roots. The first problem was the CMM was very much associated with a document-heavy, plan-driven culture which was very much in opposition to the agile software community.

But the more serious problem with the CMM was the corruption of its core value by certification. Software development companies realized that they could gain a competitive advantage by having themselves certified at a higher level than their competitors - this led to a whole world of often-bogus certification levels, levels that lacked a CertificationCompetenceCorrelation. Using a maturity model to say one group is better than another is a classic example of ruining an informational metric by incentivizing it. My feeling that anyone doing an assessment should never publicize the current level outside of the group they are working with.

It may be that this tendency to compare levels to judge worth is a fundamentally destructive feature of a maturity model, one that will always undermine any positive value that comes from it. Certainly it feels too easy to see maturity models as catnip for consultants looking to sell performance improvement efforts - which is why there's always lots of pushback on our internal mailing list whenever someone suggests a maturity model to add some structure to our consulting work.

In an email discussion over a draft of this article, Jason Yip observed a more fundamental problem with maturity models:

“One of my main annoyances with most maturity models is not so much that they're simplified and linear, but more that they're suggesting a poor learning order, usually reflecting what's easier to what's harder rather than you should typically learn following this path, which may start with some difficult things.

In other words, the maturity model conflates level of effectiveness with learning path“

Jason's observation doesn't mean maturity models are never a good idea, but they do raise extra questions when assessing their fitness. Whenever you use any kind of model to understand a situation and draw inferences, you need to first ensure that the model is a good fit to the circumstances. If the model doesn't fit, that doesn't mean it's a bad model, but it does mean it's inappropriate for this situation. Too often, people don't put enough care in evaluating the fitness of a model for a situation before they leap to using it.