Software and Obama's Victory

Barack Obama's victory in the 2008 Presidential campaign included a significant contribution from software - particularly using the Internet. But perhaps the most interesting aspect was the interplay between advances in software and developments in the human organization of the campaign.

30 July 2009

This article is based on the keynote that Zack Exley and I gave at QCon London 2009

Were it not for the Internet, Barack Obama would not be president.

It's perhaps rather natural for those who live in the internet to claim that the internet was the reason for Barack Obama's victory in the 2008 presidential elections. Although I'd doubt that the internet was the decisive factor in the presidential contest with John McCain, it certainly was a big help. And the internet was probably a necessary factor in his primary win over Hilary Clinton, who was considered a sure-thing front-runner before the primaries started in earnest.

While we can't claim any big part in Obama's internet triumph, a number of ThoughtWorkers were involved in writing software for the Obama campaign 1. I popped in occasionally to see how things were going along and got quite interested in the way software was being used in the political process. I was keen to see more said about this and at QCon London in 2009 my colleague Zack Exley and I gave a keynote about the role of software in Obama's victory.

1:

In the General Election, Thoughtworks played a role on a few critical software projects with the Obama campaign: as a contractor with Blue State Digital, the Democratic National Committee and Obama for America. Different teams of ThoughtWorkers worked on a backend scaling project, completed a grassroots organizing application for volunteers called Neighbor to Neighbor and completed the Obama FaceBook application.

As you read this, be aware that it presents a somewhat limited perspective. The source of information for this article are my colleagues who worked on the Obama campaign. I have not attempted to contact and integrate opinions from the rest of the many people who took part in the campaign. Nor have I tried to draw the net wider and look at other campaigns and the efforts of other parties. It would be interesting to do so, but my time and energy is limited. I hope that what I did learn is worthwhile to pass on.

Internet Campaigning Stirs

When Al Gore lost to George W Bush in 2000, software played a very small role in the workings of a political campaign. Scattered PCs on desks doing regular office tasks were the limit of software's influence. Internet sourced did actually raise about $1 million, but nobody took any notice 2. (Which is ironic considering Gore played a significant part in the politics of launching the Internet.)

2:

Another way of looking at the change over the years was the number of campaign staffers focused on the internet. For Gore in 2000 it was just a handful, for Kerry in 2004 it was 60-70, while for Obama it was a few hundred.

The presidential campaign of Howard Dean in 2004 alerted a lot of people to the way the internet could influence the political process. Much of Dean's support, which propelled the candidate from an unknown to a serious contender, came from activity on the internet.

What really did it for Dean was the 2nd quarter of 2003 - he raised more ($8m) than the Big Money candidates Kerry ($5m) and Edwards ($5m). It was the watershed moment when online supporters learned their power to put an insurgent ahead of the front runner. Dean's internet team put up a thermometer (in the image of a baseball bat) that showed progress toward the goal of $8m. People went wild, using blogs, their personal email, etc... to get others to donate. The campaign also used a growing email list to drive contributions, which was the primary source.

-- Zack Exley

While Dean didn't win the nomination in 2004, he and his campaign still garnered a lot of influence in the Democratic party. Dean went on to become the chairman of the Democratic National Committee (the body that runs the Democratic party nationally) and led much of the organizing that laid groundwork for the 2006 and 2008 elections.

The software also lived on. During the campaign the software was written in very much an ad-hoc manner. A bunch of geek volunteers, and a few who joined the campaign staff, got together and started throwing together whatever they could using a LAMP stack with PHP and MySQL. At the end of the campaign a number of these geeks decided to start a company to build a permanent base of this software for future campaigns. This company, Blue State Digital, played a role in congressional races in 2006 and, crucially, Obama's primary and presidential campaigns.3

3:

Blue State Digital have turned into a considerable organization over the last few years, with over a 100 clients internationally. Indeed their success as a commercial organization has been a source of controversy, as many political software activists consider their publicity about their role in Obama's victory to have been excessive.

Changing the Organizational Dynamics of Campaigns

The use of the internet caught a lot of attention, but there was also something else going on - a change in the organizational dynamics. My colleague Zack Exley likes to tell a story of how this organizational structure mutated together with the application of the software.

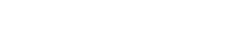

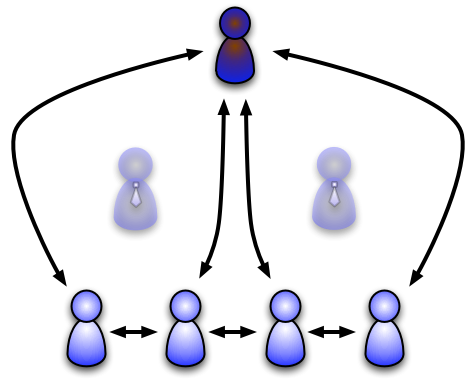

In the pre-Dean times, campaigns were very much a hierarchic command-and-control structure. The campaign center gave instructions to the immediate descendents in the hierarchy and received reports from them. In this the campaign was very much like any command-and-control organization.

Figure 1: A command-and-control organization has the campaign leadership directing campaign staffers who direct volunteers.

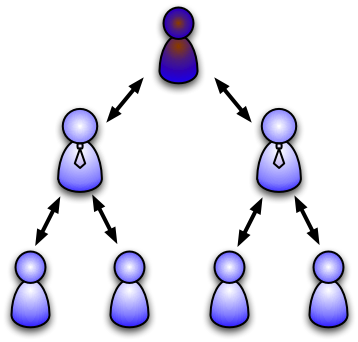

The big shift with the Dean campaign was a shift towards a peer-to-peer model, where individual volunteers, often outside of any formal campaign structure, got together to do things.

The geeks and technology enthusiasts saw this as the way of the future and sought to utilize patterns found in peer to peer networked systems and open source software development. Dean activists used blogs for communication, meetup.com and custom Dean tools for organizing.

-- Zack Exley

Figure 2: A peer to peer organization has volunteers communicating directly with each other.

This was the early days of blogs, which gave lots of people the chance to have a platform and comment on issues and campaign strategy.

Along comes this campaign to take back the country for ordinary human beings, and the best way you can do that is through the Net. We listen. We pay attention. If I give a speech and the blog people don't like it, next time I change the speech.

-- Howard Dean

A peer-to-peer approach like this creates great energy amongst individual volunteers, often engaging people who aren't likely to get involved in a formal campaign. But it lacks direction - in the Dean campaign, this became evident in Dean's surprisingly low 3rd place finish in the Iowa caucus (the first of the primary contests). This leads us to the mass-organization model, which, thanks to the internet, was developing in parallel with the peer-to-peer model.

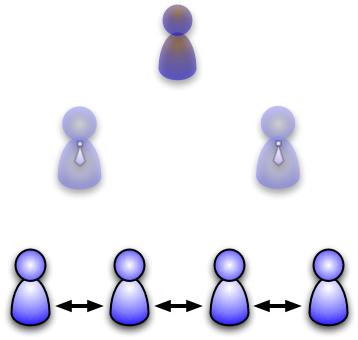

Figure 3: Mass organization has the campaign leadership direct the volunteers directly

With this model, the focus is on direct contact from the campaign leadership to activists on the ground, avoiding middle layers of organization present in the command-and-control model. MoveOn.org, an activist organization 4, is a good example of this model. MoveOn became a particularly powerful force in the Democratic party due to its opposition to Bush's invasion of Iraq.

4:

MoveOn was formed at the time of the impeachment saga of Bill Clinton - the name coming from a petition to “Censure President Clinton and Move On to Pressing Issues Facing the Nation”.

Mass-organization is a common approach - used by MoveOn, and many established NGOs. But it differs from peer-to-peer in that they don't support, and indeed sometimes discourage, getting their membership to work together in the ad hoc self-organizing mode of peer-to-peer.

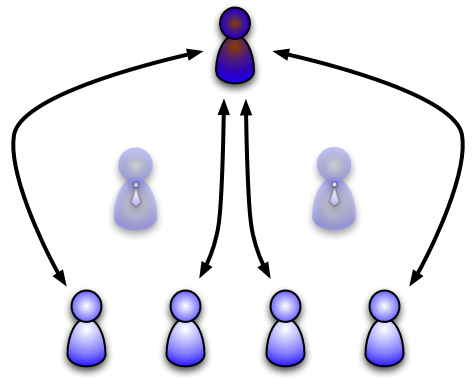

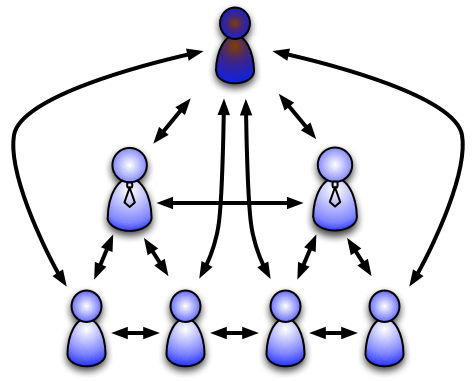

One of the main differences between the Obama campaign and its predecessors was that it fused the mass-organization and peer-to-peer models. It directed activities from the center, but also encouraged peer-to-peer collaboration. Here's an example of this fusion. An important part of the software for both the Dean and Obama campaigns is event planning software to help volunteers plan meetings. In the purely peer-to-peer mode a volunteer decides to have a meeting on a pressing topic, say health-care. They go to the event planner and enter a meeting date, time, place, topic, capacity etc. They can advertise it in the various social groups that they've set up in the system. Another volunteer who uses the same political website may see the meeting advertised in the online group, or might search for upcoming local meetings. The guest volunteer can then use event planning software to RSVP to the meeting, giving the host an idea of who's coming.

Weaving in the mass-organization model, the key difference is that the process can be kicked off by the campaign leadership. They can decide that they would like to see a coordinated push to discuss health care over the next couple of weeks. So they suggest to volunteers that they may like to try and organize meetings around this. They may provide catalysts such as articles to read or DVDs to watch. This creates a buzz around the topic that makes it more likely that meetings get set up. This buzz reaches out to potential attendees as well who are now more likely to try and find local meetings on the topic.

Figure 4: Fusing the mass organization and peer-to-peer models.

Internet tools like this played a very visible part of the Obama campaign. MyBarackObama.com, an instance of Blue State Digital's software, was the internet face of the Obama campaign 5. “Mybo”, as it was referred to, supported groups 6, event planning, letter to the editor 7, and a host of other ways to allow individuals to contribute to the campaign. But although Mybo was a very visible part of the Obama Campaign's software arsenal, it wasn't the only piece. Furthermore the organization pattern developed further from a simple fusion of the peer-to-peer and mass-organization models. But to explore these aspects I have to return to an area that I've been skipping over - the field organization.

5:

Since the election my.barackobama.com has morphed into “Organizing For America” a website run by the Democratic National Committee. It's being used to coordinate activism for various efforts in conjunction with Obama's agenda. Although Obama is now President, this is far from giving him control of policy in the US political system. In order to get anything done, he has to push initiatives through Congress and his team believes that the same grass-roots efforts that was successful in his campaign can help ferment the pressure on Congress to help.

6:

The groups feature allows a Mybo user to find and join groups, which was one of the first things people tended to do once registered with Mybo. These groups were formed in all sorts of different ways. Some were purely location-oriented, pulling together supporters in a single neighborhood. Others would bring people together due to profession or workplace, yet others focused on issues. Indeed one of the most popular groups on Mybo was one formed to oppose Barack Obama's position on FISA and try to influence him to change his mind.

Group development is entirely user based - people can form groups however they like, with little restrictions. Group formation thus mostly followed the peer-to-peer organizational model, with people forming groups in an ad hoc way.

The features of Mybo groups are familiar to anyone who has used various social group software on the internet: mailing list, event calendars, member directory. The kind of thing that's boringly common for most geeks, but still relatively new to many involved in the campaign. This allowed the group to coordinate their activity. Mybo also provided a blogging service, so that volunteers could easily post to a blog, either individually or as part of a group. Again this was not a new service, but it allowed people new to blogging to explore the technique in a way that was integrated with the campaign.

7:

The “letter to the editor” feature helped supporters write letters to newspapers advocating a particular position. In use a supporter would search to find local newspapers for her area, and then get assistance to compose a letter to that newspaper. Early implementations of this feature included sample text to help composing the letter, but this fell out of favor as it led to too many letters which obviously came from the same source. So later advice was more list of arguments to cover in the letter, to encourage writers to make a more individual expression.

Knowing About the Voters

Reading news stories about political campaigns you come across the terms “air-war” and “ground-war”. The air-war refers to the campaign conducted on television (and to an increasing extent over the internet) while the ground-war refers to feet on the ground. These feet belong to volunteers who go from door to door canvassing. Canvassing is all about using individual contact to get more voters and to get your voters to the polls.

The basic action of canvassing is pretty simple. Get hold of a bunch of eager volunteers. Identify some households to canvass. Take the households and allocate each one to a volunteer - a process referred to as turf cutting. For each volunteer prepare a walk packet - a list of households that that volunteer should canvass. Set the volunteers in motion. Then once the canvassing is done, collect the walk packets - because not just do the walk packets contain information about who to canvass, they also contain questions for the canvassers to ask to gather more information about the households.

The trick with this is to find the most useful households for the canvassers to talk to, so that their time is spent most effectively. Crudely, this means dividing households into three groups.

- Firm opponents: These households you want to ignore. It's extremely unlikely you'll change their minds, and effort to do so is likely to be counter-productive for them, you, and the canvasser.

- Undecideds or wavering: these people are those you want to persuade to support your side. You'll need to know what issues they most care about so you can figure out what information is likely to bring them into your fold.

- Firm supporters: good news to have, but not enough to leave alone. There are two things you want from supporters. First you want to ensure they actually go to the polls and vote on the day. Secondly you want to see if they will volunteer and help to canvass more people.

I talk about households here. It's true that there are plenty of people that live together but have different political opinions, but most of the time the members of the same household all vote the same way. So households are a commonly used unit in canvassing.

It doesn't take too much imagination to realize that keeping track of all this information about households is a perfect task for a computer. Indeed by the 2006 elections we started hearing stories like this:

One suburban African American woman in Ohio, for example, told us that though she tends to vote Democratic, she was deluged in 2004 with calls, e-mail messages and other forms of communication by Republicans who somehow knew that she was a mother with children in private schools, an active church attendee, an abortion opponent and a golfer.

-- LA Times

The Republican system discussed here is their Voter Vault, which builds up a detailed database of voters. The Democrats trailed the Republicans in this area but made a determined push between 2005-8, led by my old colleague Josh Hendler, to catch up. In order to make use of this data the Democrats use another system - The VAN.

Like Blue State Digital, The VAN began as an ad-hoc bunch of development as part of one particular campaign, in this case Tom Harkin's Iowa Senate campaign in 2002. Also like Blue State Digital, that software was taken into a company for longer term development - Voter Activation Network, usually called VAN. The VAN was used by various state campaigns in 2004, but by 2008 the Democrats had a single VAN instance loaded with a copy of the Democrats' national voter database to use nationally called VoteBuilder (but still often referred to as The VAN, so I'll call it that here). Unlike Blue State Digital, The VAN is a .NET application with Visual Basic, SQL Server and ASP.NET. I can't help but wonder which cultural difference is greater: Democratic/Republican or .NET/LAMP.

The LA Times quote above sounds a bit scary - that the political parties know that much about you. The truth however is a bit more prosaic. The basic source of information about voters comes from voter rolls, basic voter data kept by each state in its own incompatible format. Voter rolls will give you names, addresses, party affiliations 8, and a record of voting activity. The record of voting activity, which covers both the elections and the primaries, doesn't tell you who they voted for, just whether they voted at all. But that information is valuable as it gives you a sense of whether they are likely to vote.

8:

When you register to vote in the US, you are asked if you wish to register for a party. You don't have to, and registering for a party doesn't commit you to voting for, or being a member of that party. In some states you can only vote in a primary for the party you are registered with.

This information is augmented by other data that can be bought on the open market. A good example of this is magazine subscriptions - which might explain how they knew she was a golfer.

A good chunk of the data in The VAN is aggregate data. You don't know who a person voted for, but you do know what the overall voter tally was for a particular precinct 9. So if our example woman was lived in a precinct that voted 80% Democrat, that might explain why she was originally tagged that way. Similar aggregate data exists for race, church attendance, views on issues, where children get schooled. In all likelihood the Republicans didn't have that data matched to her individually, it was just that the aggregate data happened to align right up in her case.

9:

A precinct is an organizational clump of households - usually people who vote at the same polling station.

Once a canvasser's been round to visit, much of this information can be marked individually. Even without the persuasive aspects, canvassing can be valuable for just information gathering, in particular since much of this data is out of date. One of the most useful things a canvasser can do is update addresses and phone numbers that have changed.

One impact of The VAN is that this data can be got at more easily and more widely. Another impact, is that it can simplify the planning of canvassing. The VAN provides queries that allow users to look for suitable voters - eg people within a certain age range in a neighborhood - and display them on a map. This helps make an initial cut of households for canvassing. The user can then cut the turf for individual volunteers using the map to help cluster people together. Then The VAN can print out walk packets. The ease of getting maps these days allows the walk packets to mark the households on a map, which makes things much easier for the volunteer.

The VAN is also helpful once the walk packets come back. The polling questions are tagged with bar codes to make data entry easier. So the user can swipe the code for “voter supports Obama” and then swipe each household form for which that's true. Bar codes are a great way of collaborating between computer and print-outs.

As well as tracking voters, The VAN also helps track volunteers - keeping track of who has agreed to go to what events. The upshot of all this is that it becomes easier to carry out the various tasks that an organizer needs to do, and easier for someone more experienced to run an eye over what's going on. This is rather handy due the final shift in Zack Exley's model of political organizational dynamics.

Rethinking the Field Organization

While the fusion of peer-to-peer and mass-organization models are good at energizing a base of individual volunteers, they rather ignore the field organization. But the field organization remains a vital part of effective campaigning. The last organizational element in the Obama campaign was a shift in the way the field organization was run. As with many things this came through necessity and dovetailed with the capabilities that software, in this case The VAN, enabled.

As Obama went up against Hilary Clinton in the primaries, his campaign faced a big problem with the field organization. Clinton was already well-established with local Democratic party organizations. Obama had a lot of enthusiastic individuals, but not the organizational depth needed to win the primaries.

The organization shift was to change the role of paid staffers in the campaign. Traditionally paid staffers were primarily responsible for organizing volunteers, for example organizing canvassing as I discussed above. In Obama's campaign the paid staffer's role shifted to finding, recruiting, and supporting volunteer organizers. With this model, canvassing was organized by volunteers with the staffer acting as adviser.

Staffers would begin by finding likely volunteer organizers and get them into small teams. The campaign then ran a series of training classes where the teams would learn how to do the various activities involved in running a local volunteer group. They would then keep contact with the staffer for further help and advice.

Figure 5: The final evolution of Zack's organizational model is to fully connect everyone at all levels

Zack refers to this as the campaign version of “splitting the atom” because it greatly increases the reach of staffers and the speed with which a field organization can get up and running. Furthermore it energized many volunteers by allowing them to do more. Rather than just turning up to knock on some doors or make some calls, the volunteers could get involved in organizing that activity for themselves and others.

The VAN helped this work by allowing volunteer organizers to make walk packets and run canvasses from home. Volunteers' homes became campaign offices and “staging locations” for canvasses and phone banks. Using The VAN made all of this both easier to learn and quicker to do, both of these are important to allow volunteers to do the organizing since they tend to be short of experience and time. Furthermore the access to data allowed the staffers to keep and eye on what was going on so they could collaborate effectively with the volunteers. Agile software people like me argue that open access to project plans enable everyone to get involved - which boosts both the effectiveness of the planning and the motivation of those doing the work. Opening up the planning of canvassing is a similar notion for volunteers.10

10:

The Obama campaign was the first to allow volunteers rather than paid staffers to use The VAN. This required some tweaks to The VAN from earlier campaigns such as more robust permissioning.

Neighbor to Neighbor

The turf cutting and walk packet preparation tools in The VAN make a big difference to the field organization and thus for overall campaign. But one of the big problems that the Obama campaign had to deal with was the lack of a field organization in most states - including such populous Democratic strongholds as New York and California. This led to enhancing Mybo with similar tools under the name “Neighbor to Neighbor”. This allowed volunteers to carry out this kind of work directly with no field organization in place.

The result is, to some extent, duplicate functionality between The VAN and Mybo. But there is still a significant difference in target audience. The VAN is intended to be a tool for field organizations, and the fact that the Obama campaign made such effective use of volunteers within the field organization doesn't alter the point that those volunteers are still working within the field organization's structure. Mybo is aimed at the broader volunteer community, so its turf cutting tools allow anyone to organize canvassing in this kind of way.

The campaign used both The VAN and Mybo for turf cutting - using The VAN when working with the field organization and Mybo for more casual volunteer use. The campaign organized building integration between The VAN and Mybo, so that voter data in The VAN could be available to volunteers using Mybo and survey results captured in Mybo could augment the data in The VAN.

More important than duplicating the door-to-door aspects of The VAN, Neighbor to Neighbor added the capability to support phone canvassing. Phone canvassing is particularly important in a presidential election since candidates take states on a winner-take-all basis. There's little point for democratic supporters in Massachusetts to canvass their neighbors since Massachusetts was a safe win for Obama.

The Obama field operation only existed in about 12 states in the general election. So Neighbor to Neighbor was for all the volunteers in the other states, where there was no staff. The field campaign was only run in the “swing” or “battleground” states. Before the web, those volunteers had nothing meaningful to do. Because additional democrat votes in California or New York don't matter. But Neighbor to Neighbor allowed a sort of activist arbitrage - where those California and New York volunteers could call Florida and Ohio. The Kerry campaign (2004) and MoveOn.org (2006) had both built tools to do this but the Obama campaign was able to do it on an unprecedented scale.

-- Zack Exley

Since anyone can use Neighbor to Neighbor to look at campaign data and upload new data, it raises a question of what happens should Republican supporters use it. There's nothing to prevent this, raising concerns about bad data getting into the system. On the whole, the campaign didn't think there was much bad data getting in.

There was a limit to how much data you could get. You could get one batch, and then you had to report in results before you could get more. There was automated detection of fraudulent input. It's surprisingly easy to detect when someone is putting in false data. And the fact is - and this has been learned repeatedly by MoveOn, Dean, Kerry, Obama and others - that opponents don't want to waste their time doing insignificant damage to the other side. They'd rather go do something for their own candidate.

-- Zack Exley

Staffers and volunteers were encouraged to keep an eye on data in their area. Not just did this watch out for bad data it also got volunteers more familiar with people in their area.11

11:

Could you discover private information about your neighbors? In practice this was limited because you only got names and addresses of targeted voters in your general area.

The Big Spam Gun

Much of the attention to the role of software in Obama's campaign focused on new web tools. Yet perhaps the most important part of the software toolkit was the mailing list. By the end of the campaign some 13 million people had added their email addresses to the campaign's email list. The challenge was to compose, send, and log all these emails so that an email ask could be sent out to the whole list within a few hours. More targeted asks 12 could be sent out on subsets of the list as well.

12:

An “ask” is a request made of a volunteer to do something. It seems to be an increasingly common noun in activist circles.

The mechanics of getting out so many emails is an interesting problem, but in the end there's not much point if all the emails end up in a virtual trash bin. As well as pushing out emails, the campaign also worked to make the content of the emails more involving. Rather than simply asking people to do something, the campaign tried to use a style where they would describe the background to a situation, explain how they intended to deal with it, and then suggest ways in which the recipient could help. By knowing the back-story the volunteer feels more connected to the campaign and is also more able to come up with their own activities that fit in with the tactics. It's just about telling people what to do, but also why.

As well as the email spam gun, the campaign also started to work with SMS. When they were contemplating the Vice-Presidential pick, the campaign said they would make the announcement by an SMS message broadcast and suggested that people should sign up so they would get this information quickly. This allowed the campaign to build up a sizeable SMS list for later asks.

Video

During the 2004 campaign, many Democrats were keen on using Video. One of the frustrations of many people in politics is that the major news stations carry only tiny snippets of even the most important political speeches, reducing the most carefully constructed arguments to sub-minute sound-bites. However it proved just too difficult to set a video capability up in 2004 that could easily reach a large audience who weren't necessarily that tech-savvy.

This lack of video would have been particularly frustrating to Obama's supporters as he's widely considered to be an unusually effective speaker. Fortunately by 2008 we'd seen the rise of YouTube which provides a seasoned and very widely used mechanism for distributing video. The campaign used YouTube videos extensively, and it was pleasing to note that there was an appetite for even fairly hearty video fare. Obama's speech on race, a thoughtful 40 minute long oration, gathered several million views.

Video also played a role in emails. Many of the email asks were delivered by providing a video link that would allow campaign leaders to talk more directly to volunteers. This helped in composing emails that provided a detailed background to asks.

Looking Forwards

The Obama campaign has led many people to feel that there is a sea-change in politics - that grass-roots efforts can make a difference to national politics. As I mentioned earlier on this is less because Obama won the presidential election (the Democrats had the advantage) so much as Obama's victory over Hilary Clinton in the primaries.

The next question is what do these changes in organizing model, enabled by software, mean for further political action. The Obama machine is now pushing to get people involved in grass-roots action to change the US health care system. Many people believe that this kind of grass-roots action is the only way of beating powerful corporate interests that support the status-quo in US health care.

Certainly this kind of thing is where my interests lie. I certainly have my political views, many of which are sympathetic with many of those involved in this effort. But more fundamentally I'm in favor of tools, whether software or organizational, that give everyday people more influence on politics. Democracy relies on the engagement of everyday people in the way the country is run. It's too easy for layers of bureaucracy and money to get between The People and their government. If software can help cut through that, then I think that's a worthy cause.

Footnotes

1: Thoughtworks's involvement

In the General Election, Thoughtworks played a role on a few critical software projects with the Obama campaign: as a contractor with Blue State Digital, the Democratic National Committee and Obama for America. Different teams of ThoughtWorkers worked on a backend scaling project, completed a grassroots organizing application for volunteers called Neighbor to Neighbor and completed the Obama FaceBook application.

2: Internet Staffers

Another way of looking at the change over the years was the number of campaign staffers focused on the internet. For Gore in 2000 it was just a handful, for Kerry in 2004 it was 60-70, while for Obama it was a few hundred.

3: Blue State Digital

Blue State Digital have turned into a considerable organization over the last few years, with over a 100 clients internationally. Indeed their success as a commercial organization has been a source of controversy, as many political software activists consider their publicity about their role in Obama's victory to have been excessive.

4: MoveOn

MoveOn was formed at the time of the impeachment saga of Bill Clinton - the name coming from a petition to “Censure President Clinton and Move On to Pressing Issues Facing the Nation”.

5: Mybo since the election

Since the election my.barackobama.com has morphed into “Organizing For America” a website run by the Democratic National Committee. It's being used to coordinate activism for various efforts in conjunction with Obama's agenda. Although Obama is now President, this is far from giving him control of policy in the US political system. In order to get anything done, he has to push initiatives through Congress and his team believes that the same grass-roots efforts that was successful in his campaign can help ferment the pressure on Congress to help.

6: Mybo's groups

The groups feature allows a Mybo user to find and join groups, which was one of the first things people tended to do once registered with Mybo. These groups were formed in all sorts of different ways. Some were purely location-oriented, pulling together supporters in a single neighborhood. Others would bring people together due to profession or workplace, yet others focused on issues. Indeed one of the most popular groups on Mybo was one formed to oppose Barack Obama's position on FISA and try to influence him to change his mind.

Group development is entirely user based - people can form groups however they like, with little restrictions. Group formation thus mostly followed the peer-to-peer organizational model, with people forming groups in an ad hoc way.

The features of Mybo groups are familiar to anyone who has used various social group software on the internet: mailing list, event calendars, member directory. The kind of thing that's boringly common for most geeks, but still relatively new to many involved in the campaign. This allowed the group to coordinate their activity. Mybo also provided a blogging service, so that volunteers could easily post to a blog, either individually or as part of a group. Again this was not a new service, but it allowed people new to blogging to explore the technique in a way that was integrated with the campaign.

7: Mybo's letter to the editor

The “letter to the editor” feature helped supporters write letters to newspapers advocating a particular position. In use a supporter would search to find local newspapers for her area, and then get assistance to compose a letter to that newspaper. Early implementations of this feature included sample text to help composing the letter, but this fell out of favor as it led to too many letters which obviously came from the same source. So later advice was more list of arguments to cover in the letter, to encourage writers to make a more individual expression.

8: Party Affiliations

When you register to vote in the US, you are asked if you wish to register for a party. You don't have to, and registering for a party doesn't commit you to voting for, or being a member of that party. In some states you can only vote in a primary for the party you are registered with.

9: Precincts

A precinct is an organizational clump of households - usually people who vote at the same polling station.

10: Opening The VAN

The Obama campaign was the first to allow volunteers rather than paid staffers to use The VAN. This required some tweaks to The VAN from earlier campaigns such as more robust permissioning.

11: Privacy in Neighbor to Neighbor

Could you discover private information about your neighbors? In practice this was limited because you only got names and addresses of targeted voters in your general area.

12: Ask

An “ask” is a request made of a volunteer to do something. It seems to be an increasingly common noun in activist circles.

Acknowledgements

I wrote this article very much on the back of conversations with my colleagues about the work they did on the campaign. In particular I was greatly helped by Zack Exley and Josh Hendler who both have a long history of involvement with technology for progressive causes.

Significant Revisions

30 July 2009: First Published